|

|

|

Gloriæ Dei Cantores

Elizabeth C. Patterson, Director; conducted by James E. Jordan, Jr.

Berlioz Historical Brass

Ben Peck, buccin; Phil Humphries, ophicleide

Douglas Yeo, serpent; Ronald Haroutunian, bassoon

Members of the Boston Symphony Orchestra

Keisuke Wakao & Robert Sheena, oboe

Thomas Martin & Craig Nordstrom, clarinet

Richard Sebring & Jonathan Menkis, horn

Richard Ranti, Suzanne Nelsen & Gregg Henegar, bassoon

Douglas Yeo, serpent and contrabass serpent

Deborah DeWolf Emery, piano

Jennifer Ashe, soprano

Craig Kridel and Phil Humphries, serpent

Craig Kridel, cupped bells

Undertaken with the kind assistance of Berlioz Historical Brass, produced by Douglas Yeo

Brad Michel and Anthony DiBartolo, engineers

Digital editing and mastering by Brad Michel (Clarion Productions)

Graphic design and layout by Wayne Wilcox

BHB CD101 ~ Total time = 77:04

Recording sessions took place in April 2002, March 2003 and May 2003 at

Symphony Hall, Boston, Massachusetts and The Church of the Transfiguration, Orleans, Massachusetts.

Le Monde du Serpent was released on October 3, 2003

Return to LE MONDE DU SERPENT Page | Order LE MONDE DU SERPENT | Read reviews of LE MONDE DU SERPENT

In 1994, I had my first encounter with the historical musical instrument knows as the serpent, invented in 1590 in Auxerre, France, by Canon Edmé

Guillaume to accompany chant in the church. The story of my first encounter with the serpent, which included the first performances in North America and

Asia of Hector Berlioz's Messe solennelle is told elsewhere in my website, in my article

TEMPTED BY A SERPENT. Once there, you can find links to other articles on my

website relating to this most interesting of instruments, and you can get a sense of the growing passion I have for the serpent and other historical instruments

including the ophicleide, bass sackbut and buccin.

My musical life has been an exceedingly rich one. I have been a member of the Boston Symphony Orchestra (playing bass trombone and, when required, bass trumpet, contrabass trombone, serpent and ophicleide) since 1985; before that time I was a member of the Baltimore Symphony for four years preceeded by two years as a high school band director in Edison, New Jersey, three years living in New York City going to graduate school at New York University and freelancing in that remarkable city, and getting my undergraduate degree at Wheaton College Conservatory of Music (Illinois). In that time I have been a man blessed with myriad musical experiences in the orchestral, jazz and popular music worlds. I have played Broadway shows on Broadway (including "The King and I" with Yul Brenner), been a member of the Goldman Band (a professional concert band in New York City), played with the Gerry Mulligan and Dave Chesky big bands, recorded commercials and played on pop recordings, appeared on television, made nearly 100 recordings as a member of the Boston Symphony, Boston Pops and Baltimore Symphony, played every piece of orchestral repertoire I ever dreamed of playing, made movie soundtracks (with John Williams: "Schindler's List" and "Saving Private Ryan" and with Clint Eastwood, "Mystic River"). I played at the pregame show of and attended Super Bowl XXXVI (when the New England Patriots defeated the Saint Louis Rams, 20-17). I've toured the world, worked with great conductors and soloists, been in groups with players who have seemed to give me a daily lesson in artistry, substituted in fine orchestras (including the Vienna Philharmonic, the American Symphony and the Mostly Mozart Festival Orchestra). This has been a fun ride and it is a wonderful thing that I get to get up each morning and look forward to more music making at a high level as a member of the Boston Symphony.

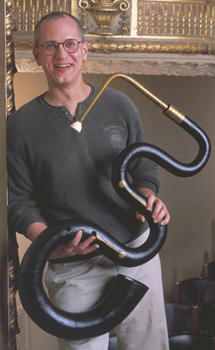

But with all of this, I'm sure many readers will understand the restless spirit which looks for even more to do, for new challenges, new ways of thinking, new territory to explore, new people to meet and new ideas to consider. When I first began playing the serpent in 1994, it was the beginning of something completely new, a foray backwards in musical time, to a repertoire that had previously been utterly unknown to me through the years I worked with a single-minded purpose to secure a position in a major modern symphony orchestra and do that job to the very best of my ability. My curiousity led one thing to another to the point where I am today, with one foot firmly both in the modern symphony orchestra and one foot in the "early music movement," playing not only the serpent, but the bass sackbut and the ophicleide. With the serpent, as I explain in the other articles on in my website which are referenced above, I have played serpent in the Boston Symphony and with Boston Baroque, playing both in concert and recording sessions. The sackbut has led me to memorable performances with both Boston Baroque and Boston's Handel and Haydn Society and performance on ophicleide have occured both with the BSO and the Handel and Haydn Society. This new life of mine with "old" music has given me not only much joy as I have experienced it, but it has also energized my bass trombone playing in the Boston Symphony in a new way. New sounds, new conductors, new people, new music, new instruments all make me appreciate even more the things which I do with the BSO from day to day. [Photo above, left, Douglas Yeo (with serpent by Baudouin, Paris, c. 1810; purchased in Paris, formerly in the collection of Andre Bissonnet) at Symphony Hall, Boston. © Michael Lutsch. All rights reserved. Used with permission.]

Le Monde du Serpent ("The World of the Serpent") is my most recent expression of this new musical life that began in 1994 on the fateful

day when I picked up a score to the Berlioz Messe solennelle, saw the piece had a serpent part, wondered what the instrument sounded

like, decided (impulsively) to purchase a modern reproduction serpent and then played it in performance with the BSO. In addition to performing on the

serpent in a variety of contexts including as a soloist with orchestra, in chamber music concerts, giving demonstrations and lectures at museums, and

writing about the serpent and its musical life in the early 19th century at

Amiens Cathedral in France, I have enjoyed my role as an exponent of the instrument, an evangelist for

the serpent, if you will, as I try to do a small part in rescuing the serpent from an undeserved extinction.

writing about the serpent and its musical life in the early 19th century at

Amiens Cathedral in France, I have enjoyed my role as an exponent of the instrument, an evangelist for

the serpent, if you will, as I try to do a small part in rescuing the serpent from an undeserved extinction.

In this, the path was prepared by the late Christopher Monk who, around 1970, began playing (and subsequently making) serpents. Monk's involvement with the serpent was responsible for the modern revival of the instrument, which had fallen into disuse in England in the 19th century and in France in the early 20th century. The photo at right shows the original members of the London Serpent Trio which Monk founded in 1976: from left to right Alan Lumsden (church serpent by Forveille, 3 keys, 1821), Christopher Monk (church serpent by Baudouin, c. 1810), Andrew van der Beek (military serpent by Robert Pretty, three keys, c. 1840), and Clifford Beven (ophicleide in B flat by E. Henri et J. Martin, 10 keys, c. 1855-1865) [photo © Berlioz Historical Brass. Used with permission.]. Other players followed Monk's lead and his Workshop continued to be the leading modern maker of serpents until his death in 1991; since that time, the Christopher Monk Workshop has continued making serpents (and cornetti) in a partnership involving Jeremy West and Keith Rogers. The London Serpent Trio continues as well since Monk's death and the retirement of Lumsden and van der Beek with Phil Humphries, Stephen Wick and Clifford Bevan forming the core of the ensemble. It is also important for me to acknowledge the extraordinary support of my friend, Craig Kridel, who as a fellow serpentist and founder of Berlioz Historical Brass has contributed mightily to not only this recording project and my life as a serpent player, but to the richness of my entire life. People like Craig who walk into your life at unexpected times are rare gifts and I am a blessed man to call him "friend." Added to Craig's quiet and overt efforts on behalf of the serpent is the work of my friend Paul Schmidt who tirelessly works to promote the serpent through "The Serpent Newsletter" and the Serpent Website. Paul's website is a one stop place where a person can find a great deal of information about the serpent, its history, repertoire, recordings, photos and much more. To Craig, Paul, the late Philip Palmer, and the many others who have been part of my journey with the serpent, I offer thanks that cannot be measured.

The 24 page booklet which accompanies Le Monde du Serpent is full of information about the repertoire, texts of the vocal works, information about the instruments used and much more. This page on my website is not meant to replace the booklet; it is meant to supplement that which appears in the booklet with more detailed information about the music, additional photos and other details which would be of further interest to people who are already experiencing the CD.

For those interested in some of the more technical details, and in the interest of giving credit where credit is due, I had some great people on the technical end who helped this CD come to be. Brad Michel of Clarion Productions was the primary engineer for the sessions and did all of the editing and mastering. I have worked with Brad on many of my solo CD projects ("Proclamation," "Take 1" and "Cornerstone") as well as CDs I've conducted with the New England Brass Band ("Christmas Joy! " and "Honour and Glory"). He is a superb engineer and editor (who has worked on hundreds of discs for Harmonia Mundi and other major labels) and is also a good friend. Anthony DiBartolo engineered one of the sessions in Symphony Hall; he stepped in when Brad was not available for that session. I knew Tony would do great work because he worked on one of the New England Brass Band sessions for "Honour and Glory" and also engineered both sessions for the band's forthcoming CD, "The Light of the World." A superb engineer as well.

Wayne Wilcox did the spectacular design work for the 24 page booklet which accompanies the CD, the tray card and the disc imprint. Graphic and visual arts are not my "thing" - I love beautiful artwork but I am utterly inept at creating it myself - I can draw stick figures and that's about it. I met Wayne through the internet a few years ago and he did the original artwork and all design for my CD "Cornerstone" which greatly pleased me. There was no question, when wishing to engage an artist/designer for Le Monde du Serpent that Wayne would be my choice. Wayne was a model of imagination and efficiency. I would give him broad ideas and provide him with images and photos; from there, Wayne came up with concept after concept. Working by phone, express mail and email, Wayne came up with what I think is one of the most beautiful designs I have ever seen in a CD. I told him that I wanted the accompanying booklet and tray card to be as interesting to the listener as is the music itself. That the booklet kept growing, from an originally planned 12 pages to 16, then to 20 and fnally to 24 created no end of adjustments Wayne had to make. His quiet manner and unflappable personality helped keep frustrations low, and the finished product was worth the many hours of work. If you are in need of a designer for a CD or another kind of project, I would be happy to put you in touch with Wayne - his work speaks for itself.

Tom Daly of Crooked Cove Records in Maine has been responsible for taking the audio and print material and turning it into a finished product. I came to Tom on the recommendation of my BSO trombone colleague, Norman Bolter and his wife, Carol Viera. Tom had worked on several of Norman and Carol's CDs and he came highly recommended. Tom has shepherded the project through beautifully, and I appreciate his attention to detail, investment of time in the project and completely honest and forthright business dealings.

And, finally, I must say a special thank you to my wife, Patricia, who has watched me become nearly obsessed at times over the last two years as this project has unfolded. It must not be easy living under the roof with a serpentist who is determined to change the world. Pat has not only been long-suffering, but she has been patient and encouraging through all of this and more. After twenty-eight years of marriage, we have learned something about each other but each day brings new surprises, joys and challenges. Working on a project as big, important and as costly as this one has given us a measure of surprises, joys AND challenges. Pat has been a great support through all of this and there is no man in the world who is as grateful for his wife than am I.

A booklet which accompanies a CD recording can be many things, and I determined early on that I wanted the booklet for Le Monde du Serpent to be very special. While the musical content and performance was certainly the main reason for making the recording, I wanted the booklet to be as interesting as the music, and to inform the reader while also not leaving questions unanswered.

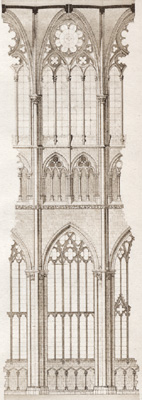

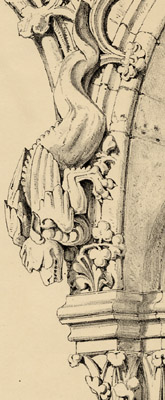

The resulting 24 page booklet is the attempt by my designer, Wayne Wilcox, and me to do this. In addition to detailed information about how this recording came about, program notes, information on the performers and their instruments, photographs, and acknowledgements, I decided on a theme to go along with the information in the booklet: the great gothic cathedral in Amiens, France.

Ever since I came to know Charles Wild's Choir of the Cathedral of Amiens which shows two serpent players playing in that great Cathedral, I have been fascinated with the architecture and musical life of that church. The link above takes you to many photos of the cathedral including photos of some extraordinary graffiti of carved serpents in one of the choir stalls.

Becasue of my own interest in the Cathedral of Amiens and its important connection to the serpent, I began collecting 19th century engravings of the Cathedral. I found it amazing how many books of engravings of great Cathedrals were available, and how many were being ripped apart and sold at auction, page by page, on eBay and other auction sites.

While one might hope the entire books were preserved for study and enjoyment, I took to collecting as many pages of engravings of Amiens Cathedral as I could find, and the result is a large collection of 19th English, German and French engravings which show architectural details of windows, buttresses and statues, along with choir stalls and much more. I selected a number of them and asked Wayne Wilcox if he could incorporate some of them into the booklet design. This he did in a wonderful way, interspersing the text and photos with thirteen engravings [Two examples of these engravings are shown on the left and right of this text; the left shows a longitudinal look at the interior of the Nave, and on the right is a detail of a gargoyle on the arcade above the West front's porch.]. I hope readers find that the inclusion of these engravings is a "valued added" aspect of Le Monde du Serpent and that more people will become interested in the remarkable construction and artwork which makes up the unique building we call a French gothic cathedral.

By the 18th century, the church in Auxerre had developed its own unique style of chant, different in both musical construction and text from

the more traditional and established Roman chant. The Gallican flavor of this chant is quite rich, and one of its outstanding features is how chant was improvised

"sur le livre" (by the book). To the chant melody, polphonic harmonies were added in various sections. The realization of this "Alleluia" was made by

Marcel Marcel Pérès, director of the Ensemble Organum. I first heard it on the CD "Plain-Chant: Cathedrale d'Auxerre XVIII siecle" by the Ensemble Organum conducted

by Marcel Peres (Harmonia Mundi HMA 1901319) to which I added the serpent part on the chant melody in the tradition of French churches at that period.

Marcel Marcel Pérès, director of the Ensemble Organum. I first heard it on the CD "Plain-Chant: Cathedrale d'Auxerre XVIII siecle" by the Ensemble Organum conducted

by Marcel Peres (Harmonia Mundi HMA 1901319) to which I added the serpent part on the chant melody in the tradition of French churches at that period.

After I had decided to include choral works on Le Monde du Serpent, the choice of a choir was an easy decision. I had long been aware of the work of the Community of Jesus in Orleans, Massachusetts, a religious community in the Benedictine tradition which makes music an important part of their devotional life. Many years ago I gave trombone lessons to two brothers at the Community; subsequently I heard their large choir, Gloriæ Dei Cantores, sing at Boston Pops Christmas concerts. Hearing Gloriæ Dei Cantores sing at Christmas made an enormous impression on me as the combination of their high artistry, positive spirit and remarkable ensemble always left me wishing I could hear more. I contacted Gloriæ Dei Cantores to inquire about the possibility of them singing on my CD as I knew they were recognized as one of the great chant choirs in the world. The happy collaboration we were able to arrange is heard on Le Monde du Serpent. For the "Alleluia," we utilized the 14 voice Gloriæ Dei Cantores Schola, a select group of singers who observe the liturgical hours and sing chant each day. Conductor James E. Jordan, Jr. had prepared the choir exquisitely and working with them in their stunning new church, the Church of the Transfiguration was an intensely moving musical and spiritual experience. The photo at left shows me with the Gloriæ Dei Cantores Schola during the recording of "Alleluia" in the Church of the Transfiguration, Orleans, Massachusetts. [Photo © Berlioz Historical Brass; used with permission.]

Like all other instruments, the serpent has a rich body of study material for students wishing to become proficient players. Jean-Baptiste Métoyen, a bassoon player at the Chapelle Royale in Versailles wrote what is believed to be the first method book for serpent and it is with a nod to him that his "Etude 8" appears second on my CD. Written around 1792, Métoyen submitted his method for serpent for use by the Paris Conservatory. The sad, somewhat shocking tale of how Métoyen's work was nearly summarily dismissed by François-Joseph Gossec (the president of the Conservatory) and Nicholas Roze (the Conservatory's librarian) in favor of Gossec and Roze's own method is told by Benny Sluchin in his detailed article, "The Venomous Affiar of the first Serpent Method" (Historic Brass Society Journal. Volume 14, 2002. pp. 309-335). Métoyen's method is full of technical exercise in a variety of keys - Étude 8 is representative of his book with a light character and technical demands which would put even a modern euphonium or trombone player through his paces.

The method by Schiltz (his first name is unknown) dates from somewhat later (1836) and has a selection of etudes and duets, many of which are based on operatic themes which would have been known to the student. Études 1 and 3 present somewhat different styles of Schiltz's etudes, although both require a nimble technique, with Etude 1 also requiring a smooth legato style in rapid passage work.

The music to these etudes came to me courtesy the Christopher Monk Collection. Monk also published these études in his book, "The Serpent Player," a privately issued book which was printed in a limited edition, containing selections from a variety of serpent tutor books along with translations of some serpent book texts and transposition of some duets and etudes to more comfortable keys.

One of the most beloved pieces of classical music is Johannes Brahms' "Variations on a Theme of Haydn" for orchestra. The theme of the "Variations" is the

"St. Antoni Chorale," copied by Brahms from a manuscript of a Divertimento for Winds which was attributed to Franz Josef Haydn (for a further

discussion of Brahms' work, see Donald McCorkle's book, "Johannes Brahms: Variations on a Theme of Haydn." Norton, New York. 1976. ISBN

0-393-02189-0). Shown below, members of the Boston Symphony Orchestra in performance of the Divertimento [Feldparthie] in B flat [St. Antoni

Chorale], Hob. 2:46 in March, 2003. Left to right: Keisuke Wakao and Robert Sheena, oboe; Richard Ranti, Suzanne

Nelsen and Gregg Henegar, bassoon; Douglas Yeo, serpent; Jonathan Menkis and Richard Sebring, horn. [Photo © Miro Vintoniv. All rights reserved.

Courtesy the Boston Symphony Orchestra.]

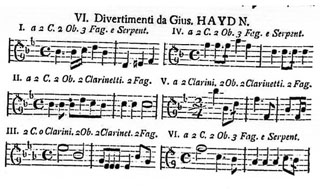

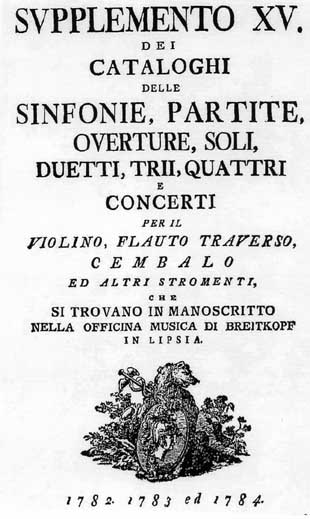

In 1870, C. F. Phol, who was at work on a biography of Haydn, showed his friend, Brahms, a copy he had made of the manuscript of a Divertimento in B flat by Haydn. The original manuscript of the Divertimento was, at that time, in the Gymnasialbibliothek in Zittau, near Leipzig (the manuscript is now found at the Sachsische landesbibliothek in Dresden). The Divertimento was one of a set of six works for winds which were published by Breitkopf between 1782 and 1784; the manuscript Pohl used for his copy has a title page which reads (translated from the Italian), "Divertimento 1 for 2 oboes, 2 horns 2 bassoons, obligato bassoon and serpent, by Josef [Giuseppe] Haydn." When Anthony van Hoboken undertook his catalog of Haydn's works (published in 1957) , he included the Divertimento in B flat as Hob: 2:46. The Divertimento in B flat was notable for two things: its spectacular second movement (which was subtitled, "St. Antoni Chorale") and the fact that it called for an unusual instrumentation including an instrument not unknown to Haydn, the serpent.

By the time Hoboken published his famous catalog, several printed editions of the Divertimento in B flat had been published, most notably by Karl Geiringer in 1932. But rumblings about the dubious authorship of the Divertimenti were already beginning to circulate. Haydn scholar H. C. Robbins Landon wrote, for the Saturday Review of Literature (August 25, 1951), a scathing piece titled, "True and False in Haydn." Robbins Landon wrote, in part:

"Another interesting case in mistaken identity concerns the six 'Zittauer' Divertimenti (the title was applied because the only MSS of these works are in the Gymnasialbibliothek in Zittau, a Saxon town near Leipzig). The works are scored for a large wind ensemble, including serpents. One of the divertimenti is already well known to every concert-goer. Its second movement is the 'Chorale St. Antoni,' which Brahms used for his 'Variations on a Theme of Haydn.' It has now been established that the whole series is spurious and that not one note was by Haydn. One of his students, perhaps Pleyel, was probably the real author."

And so, with a stroke of a pen, Haydn was no longer the composer of the famous Divertimento in B flat.

And so, with a stroke of a pen, Haydn was no longer the composer of the famous Divertimento in B flat.

Of course it was not so simple. That there had been a furious trade in spurious pieces attributed to Haydn had been well known. Publishers knew that

works by Haydn were good sellers, and if they carried pieces that had his name, there was money to be made. Without copyright protections, there

was little a composer could do to stop the traffic in works by lesser composers under a great composer's name. Robbins Landon was unequivocal, though, and

in his 1951 article, proposed a possible author of the Divertimenti, Ignaz Pleyel. For some time, the Divertimenti were often listed as being written by

"Haydn/Pleyel" or simply by "Pleyel."

At right, the title page from the Breitkopf catalog covering works published from 1782-1784 in which the Divertimenti first appeared. Above, a musical summary of the "Haydn" Divertimenti from the same Breitkopf catalog, including the Divertimento in B flat, shown as Number 1.

The trouble was that there was no evidence that Pleyel had written the works. Rita Benton's thematic catalog of Pleyel's work does not include the Divertimenti OR the "St. Antoni Chorale." It seems that Pleyel's possible authorship was likely as dubious as the claim of Haydn's own authorship. Several years later, in a letter to the Musical times (July 1960), Robbins Landon again weighed in on the subject of the famous "St. Antoni Chorale" Divertimento in response to a letter by Alan Lumsden (May 1960) which asserted that the work was "original Haydn." Again, Robbins Landon:

"With half of Haydn's genuine music unpublished, however, it seems slightly silly to publish spurious works, especially when they are (as in the case of the Zittau Divertimenti) of thoroughly second-rate calibre. After all, the melody of the St. Anthony Chorale is immortal despite, and not because of, the obscure composer who provided it with harmony and accompaniment."

Robbins Landon's continued argument against Haydn's authorship of the Divertimenti is notable for what it does not include: any reference to Pleyel. More recent scholars (Marshall Stoneham, Jon A Gillaspie, David Lindsey Clark, writing in the "Wind Ensemble Sourcebook and Biographical Guide." Greenwood Press, Number 55), provide some more balanced comments:

"Robbins Landon, noting that the Zittau source of these works is 'notoriously unreliable,' comments that their 'stylistic content. . . is totally foreign to Haydn's wind band writing.' In preparing this book, we fully expected to repeat this view. While we have no doubt that these works are not by Haydn, actually hearing these works (instead of merely hearing about them) made us reluctant to rule out a Haydn link. A common claim is that Pleyel wrote the set. This suggestion does not stand even the most superficial scrutiny. In particular, there is not the remotest sytlistic similarity to Pleyel's contemporary authentic divertimento. . .". . . Our guess - no more - is that some of these works are based on genuine Haydn material (not necessarily wind music; perhaps organ improvisations, for Haydn is known to have conducted works from the organ. . . We suspect that the composer was a competent musician who knew Haydn's style of the 1760's, perhaps a player at Eszterhaza or in the Sopron town band and who tried to imitate Haydn's style. The Esterhaza lists include several musicians present in the 1760's when Haydn's own wind music was played, present twenty years later when this set ws published, and known as competent composers. Perhaps one of them wrote this puzzling set: Franz Novotny (organist); Joseph Wolfgang Dietzl (violinist, horn player); Joseph Purksteiner (violinist and violist); Carl Schiringer (double bass player, bassoonist, flautist).

"

And so we are left with a puzzle. Haydn's authorship is questioned but not disproved, and the imposter (if there be one) has not come forward to take credit as composer of the Divertimenti. In listing this work (which, regardless who the composer may be, is still a charming piece) I have chosen to name Haydn as the composer with an editorial (?) as that is how the work is widely known, and then give the date of the first publication of the work by Breitkopf, 1782-1784. Having studied the original manuscript which is in Dresden, as well as Pohl's copy and Brahm's copy of the "St. Antoni Chorale" movement by Brahms which are in Vienna, Berlioz Historical Brass commissioned me to make a new edition of this famous work which will be published by Sarastro Music (London).

My Boston Symphony colleagues and I performed the "Divertimento in B flat" on two chamber music concerts during the winter of 2003 in preparation for my CD. While the "St. Antoni Chorale" theme was well known to them because of Brahms' appropriation of the famous theme, the Divertimento itself was new to them. To hear this famous piece in its original instrumentation (Brahms retained the original wind band scoring of the presentation of the theme, although alas, he substituted the contrabassoon for the serpent...) is an ear-opener, as the serpent brings a totally different character to the work than the contrabassoon or string bass (which are usually substituted for the serpent) and the brilliance of the oboes against the other six darker instruments is both startling and charming.

Founded in 1976, the London Serpent Trio has delighted audiences with its concerts and presentations on behalf of the reputation of the serpent. As

mentioned above, the trio's founding members, Alan Lumsden, Christopher Monk and Andrew van der Beek [Photo at right © Ian Cook], were

often joined by a fourth member, Clifford Bevan, who played both ophicleide and serpent. The London Serpent Trio today consists of Bevan, Phil Humphries

and Stephen Wick. There is no known original, historical repertoire for serpent trio (although there are duets; more on that below), so it fell to members

of the Trio to make arrangements of works suitable for performance by three serpents. The London Serpent Trio's first recording dates from 1981 when

they released "Sweet and Low" (Titanic Ti-100) which was recorded in Boston's Lindsey Chapel. The first selection on the LP (unfortunately it has not

been re-releaased on compact disc) was Alan Lumsden's arrangement of the famous march from Handel's opera "Scipio" (or "Scipione", depending on whether

the opera is sung in English or Italian). Likewise, the "Foxtrot" of Mátyás Seiber was a favorite of Christopher Monk's and it clearly shows his

keen wit - imagine, a foxtrot played on a trio of serpents!

Founded in 1976, the London Serpent Trio has delighted audiences with its concerts and presentations on behalf of the reputation of the serpent. As

mentioned above, the trio's founding members, Alan Lumsden, Christopher Monk and Andrew van der Beek [Photo at right © Ian Cook], were

often joined by a fourth member, Clifford Bevan, who played both ophicleide and serpent. The London Serpent Trio today consists of Bevan, Phil Humphries

and Stephen Wick. There is no known original, historical repertoire for serpent trio (although there are duets; more on that below), so it fell to members

of the Trio to make arrangements of works suitable for performance by three serpents. The London Serpent Trio's first recording dates from 1981 when

they released "Sweet and Low" (Titanic Ti-100) which was recorded in Boston's Lindsey Chapel. The first selection on the LP (unfortunately it has not

been re-releaased on compact disc) was Alan Lumsden's arrangement of the famous march from Handel's opera "Scipio" (or "Scipione", depending on whether

the opera is sung in English or Italian). Likewise, the "Foxtrot" of Mátyás Seiber was a favorite of Christopher Monk's and it clearly shows his

keen wit - imagine, a foxtrot played on a trio of serpents!

While Christopher Monk passed away (in 1991) before I had the opportunity to meet him and I have never met Alan Lumsden, I have met both Andrew van der Beek and Clifford Bevan, and in planning this CD, there was no question that I would include a serpent trio in tribute to the London Serpent Trio's original members who did so much to advance the cause of the serpent. There have been other groups over the years which have been inspired by the London Serpent Trio including the Saturday Serpent Society, or SSS (the late Philip Palmer, Connie Palmer, Robert and Tra Wagenecht) and the American Serpent Players, or ASP (a group of flexible number, including Craig Kridel, Steve Silverstein, Ben Peck, Terry Pierce, Tom Zajac and Dick Fuller). Whenever serpentists gather, it is inevitable that the repertoire of the London Serpent Trio will figure in the gathering, with selections ranging from the classical repertoire up to popular songs. Perhaps the most astonishing extension of this inspiration of the LST was the performance, at the 1989 Serpent Festival in Columbia South Carolina, of "Under the Board Walk" with an ensemble of several dozen serpents accompanied by the University of South Carolina Marching Band at the half-time show of a USC football game, and the performance of Clifford Bevan's arrangement of Tchaikovsky's "1812 Overture" with an ensemble of 50 serpents at the 1990 Serpent Festival at St. John's, Smith Square, London.

The serpent ensemble offering on my new CD is a bit more modest. Using a bit of modern technology, Craig Kridel and I recorded Handel's "March" with

me playing the top part (right channel), Craig playing the middle part (middle) and my also playing the bottom part (left). Recording engineer

Brad Michel managed the overdubbing which allowed the two of us to play the three parts. For Seiber's "Foxtrot," the decision to have Phil Humphries come

to the final recording session for my CD to play ophicleide (more on that below) offered an opportunity to record a serpent trio with three players. Phil

graciously agreed to bring his serpent AND ophicleide to the session where we recorded the "Foxtrot." [Photo, left of Phil Humphries,

Craig Kridel and Douglas Yeo, taken by Brad Michel in the

Church of the Transfiguration, Orleans, Massachusetts. ©

Berlioz Historical Brass. All rights reserved.] I played the top part (right channel), Craig played

the middle part (middle) and Phil played the bottom part (left). Because the arrangement previously used by the original London Serpent Trio

had not been officially approved by Seiber's publisher, I made a new arrangement of the piece through an agreement with Seiber's publisher (European American Music)

which is faithful to the old LST arrangement apart from the fact that I added Seiber's final note which inexplicably was left out of the LST arrangement.

To the original members of the London Serpent Trio, my thanks and

gratitude. I, and all those who play or aspire to play the serpent, are indebted to you for your inspiration and good humor! And to Christopher Monk, the

"Foxtrot" is for you, in tribute to your love of the serpent and the way in which you charmed all who heard you speak of and play your beloved instrument.

The serpent ensemble offering on my new CD is a bit more modest. Using a bit of modern technology, Craig Kridel and I recorded Handel's "March" with

me playing the top part (right channel), Craig playing the middle part (middle) and my also playing the bottom part (left). Recording engineer

Brad Michel managed the overdubbing which allowed the two of us to play the three parts. For Seiber's "Foxtrot," the decision to have Phil Humphries come

to the final recording session for my CD to play ophicleide (more on that below) offered an opportunity to record a serpent trio with three players. Phil

graciously agreed to bring his serpent AND ophicleide to the session where we recorded the "Foxtrot." [Photo, left of Phil Humphries,

Craig Kridel and Douglas Yeo, taken by Brad Michel in the

Church of the Transfiguration, Orleans, Massachusetts. ©

Berlioz Historical Brass. All rights reserved.] I played the top part (right channel), Craig played

the middle part (middle) and Phil played the bottom part (left). Because the arrangement previously used by the original London Serpent Trio

had not been officially approved by Seiber's publisher, I made a new arrangement of the piece through an agreement with Seiber's publisher (European American Music)

which is faithful to the old LST arrangement apart from the fact that I added Seiber's final note which inexplicably was left out of the LST arrangement.

To the original members of the London Serpent Trio, my thanks and

gratitude. I, and all those who play or aspire to play the serpent, are indebted to you for your inspiration and good humor! And to Christopher Monk, the

"Foxtrot" is for you, in tribute to your love of the serpent and the way in which you charmed all who heard you speak of and play your beloved instrument.

As I mentioned earlier, I first played the serpent in Boston Symphony Orchestra performances of Hector Berlioz's Messe solennelle.

The serpent has a prominent part in the Agnus Dei of the Messe, but Berlioz also wrote parts for two other

unusual bass brass instruments in the piece: the buccin and the ophicleide. The buccin (no relation to the Roman "buccina") is a type of trombone, invented

around the time of the French Revolution which has a trombone slide and a bell that is of hammered tin in the shape of a dragon's head. Brightly painted, and

with the dragon's head bell (with a tongue of tin which flaps when played loudly) behind the player, it is an impressive looking instrument if at the same time one of the

most difficult to play (since the bell is behind the player's head, there is no visual reference point in front of the player to assist with relative slide

positions; as such, playing the buccin is akin to playing a slide whistle). The ophicleide (the word comes from the Greek words for "serpent" [ophis] and

"key" [kleis]) is a keyed brass instrument which was along the evolutionary path from the serpent to the tuba; usually in C or B flat, it has 9-13 keys. By using

these three unique bass brass instruments in his Messe, the young Berlioz was making a statement in sound, looking for sonoroties

which would get the attention of listeners while also catching their eye.

As I mentioned earlier, I first played the serpent in Boston Symphony Orchestra performances of Hector Berlioz's Messe solennelle.

The serpent has a prominent part in the Agnus Dei of the Messe, but Berlioz also wrote parts for two other

unusual bass brass instruments in the piece: the buccin and the ophicleide. The buccin (no relation to the Roman "buccina") is a type of trombone, invented

around the time of the French Revolution which has a trombone slide and a bell that is of hammered tin in the shape of a dragon's head. Brightly painted, and

with the dragon's head bell (with a tongue of tin which flaps when played loudly) behind the player, it is an impressive looking instrument if at the same time one of the

most difficult to play (since the bell is behind the player's head, there is no visual reference point in front of the player to assist with relative slide

positions; as such, playing the buccin is akin to playing a slide whistle). The ophicleide (the word comes from the Greek words for "serpent" [ophis] and

"key" [kleis]) is a keyed brass instrument which was along the evolutionary path from the serpent to the tuba; usually in C or B flat, it has 9-13 keys. By using

these three unique bass brass instruments in his Messe, the young Berlioz was making a statement in sound, looking for sonoroties

which would get the attention of listeners while also catching their eye.

My performance on serpent of Berlioz's Messe was a groundbreaking event, as it was the first time an historical brass instrument had been played in the Boston Symphony Orchestra. This event, in 1994, was the seminal inspiration for the founding of Berlioz Historical Brass, a not-for-profit organization which was formally established in 2003 to "explore the role of 19th century brass." Craig Kridel is the founder of Berlioz Historical Brass and the first piece BHB commissioned is Clifford Bevan's Les Mots de Berlioz. [Photo right and below: Berlioz Historical Brass with Gloriæ Dei Cantores during the recording session for "Les Mots de Berlioz" at the Church of the Transfiguration, Orleans, Massachusetts. Photo © Berlioz Historical Brass. All rights reserved. Used with permission.]

In Les Mots, Bevan has crafted a unique and significant new piece which combines a choral presentation of the text of a letter of the 21 year old Berlioz to his friend, Albert Du Boys regarding the premiere of the Messe on July 10, 1825, with a quartet of winds including the three unique bass brasses he used in the Messe along with bassoon, making a low voice quartet. Bevan's own note, taken from the fly leaf of the score, gives an ample description of the piece:

This work is a tribute to Berlioz, a composer I greatly admire for many reasons. Unlike him I am not inclined to attempt the impossible, and while aspiring to create a well-crafted composition, I have not in any way sought to match the master.After the first performances of his Messe solennelle, in Paris on 10 July 1825, the twenty-one-year-old composer wrote to Albert Du Boys, a law student friend from Grenoble (not far from Berlioz's home town) whom he had met in his own early student days in Paris. Du Boys was interested in music and literature; Berlioz later set two of his poems to music. Through Du Boys' connexions, Berlioz obtained permission from the Head of the Department of the Arts to use the Opera orchestra in the performance (at the composer's expense), so Du Boys had several reasons for wishing to hear an account of it. When Berlioz wrote to him, ten days later, he was still in a state of high excitement, and this is reflected in the style and content of his letter.

Les Mots de Berlioz is a setting of about a third of Berlioz's communication.

In his Messe solennelle, Berlioz used several themes familiar to modern audiences as a result of his having used them again in later works. One of these, heard in the "Gratias" of the Messe, was utilised in the "Scene aux champs" of the Symphonie fantastique. I have used the "idee fixe," which appears in every movement of the Symphonie, as one of the two main themes of Les Mots de Berlioz. The other theme, which is prominent in the Symphonie but does not appear in the Messe, is the plainchant, "Dies Irae."

Elsewhere there are references to styles of melody, characteristic rhythms, textures and harmonies which are aimed at keeping in the listener's mind an awareness of Berlioz's presence, but there are no other direct quotations (so far as I know). To avoid the impression of Berlioz pastiche, I have been anxious to place his own music in an historic context.

Although the voicing of the opening chords of Les Mots is a direct reference to his experimental use of flutes to strengthen the low trombone pedal notes in the "Agnus Dei" of the Grande messe des morts, the second chord is characteristic of Poulenc and other early twentieth-century French composers.

Towards the end of the work, the choir is instructed to declaim, rather than sing, a style of enunciation favoured by Racine and other dramatists which strongly influenced not only the presentation of early French opera but also recent composers like Stravinsky (Persephone) and Honegger (Le roi David).

Recording Les Mots was, quite honestly, a thrill. I had never heard a buccin played before Ben Peck put it to his lips. The sound was a rare one, more like a covered horn than a trombone (because of the shape and construction of the bell). Phil Humphries flew over from England to play the ophicleide part, having had a lesson on the part from Cliff Bevan before departing for the United States. Ron Haroutunian, bassoon, is a friend who plays frequently as a substitute in the Boston Symphony and Boston Pops Orchestras. [Photo right : Douglas Yeo, Phil Humphries and Ben Peck at the Church of the Transfiguration, Orleans, Massachusetts. Photo © Berlioz Historical Brass. All rights reserved. Used with permission.] Gloriæ Dei Cantores sang magnificently and I can say that they truly enjoyed the piece as much as we instrumentalists did. The premiere performance of Les Mots will take place on October 19, 2003 with Berlioz Historical Brass (Ben Peck, buccin; Jay Krush, ophicleide; Douglas Yeo, serpent; Suzanne Nelsen, bassoon) with the King's Chapel Choir at King's Chapel, Boston, Heinrich Christensen, director. In a sense, Les Mots de Berlioz is the perfect piece with which to celebrate 2003, the Berlioz bicentennial year. It is a tribute to a master composer by another masterful composer, and a way to bring instruments of Berlioz's time into our own. Thank you, Cliff Bevan. We are all the richer for your splendid offering in honor of Berlioz and his instruments!

Les Mots de Berlioz is published by Piccolo Press, Winchester, England.

Clifford Bevan tells the story of how he came to compose a piece on this old American folk song, as printed on the cover of his published music

[Below, left: Photo of Clifford Bevan playing a bass horn, courtesy Craig Kridel]:

The Pesky Sarpent or On Springfield Mountain, is thought to have been composed around 1840, possibly by Nathan Torrey or Daniel or Jesse Carpenter. It tells the story of the death from a rattle-snake bite on August 7, 1761 of twenty-two-year-old Lieutenant Thomas Merrick (or Myrick) of Springfield (now Wilbraham), Massachusetts. The rattle-snake is an important element in American mythology, appearing in the first flag of the American Revolutionary Army with the warning DON'T TREAD ON ME.

The original setting of The Pesky Sarpent was slow, based on the hymn-tune The Old One Hundredth but a comic impersonator named Spear introduced Sally in his parody Love and Pizen, and this lively version inspired others found throughout the United States - not always, it must be said, with totally innocent lyrics.

(information on the subject can be found in R. Lax & F. Smith "The Great Song Thesaurus" (New York, N.Y., 1984, 2nd edition, 1989) and A. Lomax "The Folk Songs of North America (London, 1960). The words and melody are printed in J. A. & A. Lomax "Best Loved American Folk Songs" (New York, N.Y., 1947).)

No works for serpent with piano accompaniment seem to have been composed during the first 400 years of the instruments existence, so Variations on The Pesky Sarpent is without a doubt one of the first, if not the first. It received its premiere, given by the composer accompanied by Maxim Rowlands, during a concert at Bromley Music Centre, Kent (England) on June 25 1996.

The Pesky Sarpent has been recorded by many American folk singers, from Woody Guthrie to Burl Ives. Bevan's treatment of the song uses one of the poem's early tunes; such is the power of this story that Copland found it so representative of American folk lore and song that he included a variant of On Springfield Mountain in his A Lincoln Portrait. The tune and the words have changed from time to time, with the ill-fated couple seen as both Johnny and Sally or Tommy and Molly. I first performed Variations on The Pesky Sarpent on a recital in New England Conservatory of Music's Jordan Hall on March 31, 1997 with Deborah DeWolf Emery accompanying at the piano. Bevan's piece calls for a "big sound" from the piano, in the manner of Liszt, as he presents the theme and then continues with the story, a funeral and the final warning to all who would listen ("And don't get bit by a rattlesnake").

While Cliff Bevan's Variations on The Pesky Sarpent stands very well on its own, knowing the story behind the theme and some of the drama the composer is trying to portray greatly enhances a listener's enjoyment of the piece. Rather than simply print the text of the The Pesky Sarpent in the CD booklet, I thought that actually speaking the poem would add something a little different to the CD. After all, the incident which inspired The Pesky Sarpent happened in Massachusetts, a little more than an hour from my home. As a resident of New England, I thought reciting the poem my self (rather than hiring someone to do a dramatic recitation) would strengthen my own New England roots (although I suppose I will never be a true blue Yankee, being born in California, lived in New York City, New Jersey, Chicago and Baltimore before being transplanted to Boston). I must say it was a memorable moment to stand alone on stage in Symphony Hall in Boston and recite the poem several times to a completely empty hall. An orator I am not, but never was I so surprised at the sound of my own voice!

Variations on The Pesky Sarpent is published by Piccolo Press, Winchester, England.

American composer Drake Mabry lives and works in Poitiers, France where he is Director of the CEFEDEM Musique. I got to know Drake through his connection with the serpent; he is a good friend of Michel Godard, one of the leading serpentists in France, and as a composer, Drake has written several pieces for Michel. Drake has also taken up playing the serpent as well, and performances of his improvisations with Michel Godard have been heard on occasion on French radio.

Quatre Tanka was composed for Michel Godard, serpent, and Linda Bsiri, soprano and was premiered by them in 1998. The "Tanka" is

a Japanese poetic form, similar in some respects to haiku but with subtle differences. The four poems which make up Quatre Tanka were written by Drake

and they are sung in French; each is a reflection on a different subject in a subtle but strong way. dans la nuit reflects upon the

night. The serpent, after an opening outburst, settles into an ostinato on a middle "D", using four different fingerings for that note to provide subtle changes in

timbre. Later in the movement, the serpent player is asked to sing and play at the same time (this technique is called "multiphonics" although Drake calls

for the same note, "D", to be sung as it is played, giving the note a fuller and more ambiguous sound). á midi speaks of noon,

and images of insects hiding in the desert sand. The serpent opens in unison with the soprano, slightly covering the vocal part as the insects are

covered by shadows. le printemps is almost entirely whispered, both by the soprano and the serpent, as the quiet of bees passing through

flowers and flowers playing with their friends is atmospherically told. dans le village is a wild romp showing children at play in the

crowded village. The movement is entirely improvised on a pattern Drake laid out for the soloists, with the soprano starting by singing the text as fast as possible and

gradually slowing to the end, and the serpent starting as slow as possible and gradually getting faster to the end. The serpent part is free glissando apart from

the final notes (the last note is a high c#!) and the movement is one of hilarious play.

When Drake and I first connected with one another, he sent me a copy of Quatre Tanka and I immediately knew I wanted to play it. Not being much of a singer myself, I didn't know the first thing about finding the right person to collaborate with on the piece, so I asked Lucy Shelton, professor of voice at New England Conservatory of Music, if she could recommend a singer to work with me. Without hesitation she recommended Jennifer Ashe, a doctoral voice student at NEC who was an active performer and teacher in the Boston area. [Shown above, right, are Jennifer Ashe and me; the photo was taken by Anthony DiBartolo during the recording session for "Quatre Tanka".] Lucy Shelton coached Jen and me on the piece and we performed it in recital in Jordan Hall at New England Conservatory, and at the 2000 Historic Brass Festival at the University of Connecticut at Storrs, Connecticut. Collaborating with Jen is a special joy; her voice is beautiful, her pitch is impeccable and she brings a wonderful style to this music.

With Quatre Tanka, my CD is brought solidly into our new century, pushing the envelope of the technique of the instrument and giving a distinctly contemporary voice to this ancient instrument.

Quatre Tanka will be published soon by Drake Mabry Publishing which is based in San Diego, California.

Method books for serpent began to be written in the late 1700's (see the discussion of Metoyen's method above) and whether English or French, all seem

to have several common features. Most methods have some discussion of the playing of chant, as that was the primary function of the serpent until it began

to be appropriated for wind bands, military bands and the symphony orchestra). Études abound as would be expected, and most methods have a section of duets.

Method books for serpent began to be written in the late 1700's (see the discussion of Metoyen's method above) and whether English or French, all seem

to have several common features. Most methods have some discussion of the playing of chant, as that was the primary function of the serpent until it began

to be appropriated for wind bands, military bands and the symphony orchestra). Études abound as would be expected, and most methods have a section of duets.

Duets are an excellent teaching tool. When two instrumentalists play together, they must work to play in tune, match styles, and have good ensemble. I recall the years when I was taking bass trombone lessons weekly from Edward Kleinhammer (who played in the Chicago Symphony from 1945-1985) and how each lesson began with several duets played by the two of us. That was an invaluable part of each lesson, and because I benefitted so much from playing duets with my teacher, I have my students play duets with me at the beginning of each lesson I teach. The writers of the old serpent methods knew this too, for the quality of duets in the old tutors is quite high, requiring much from both players in terms of technique and style.

Hardy's method is one of the best known serpent method books, and his Duo 2 is representative of his duet material. Craig Kridel and I first played this duet at the 2000 Historic Brass Society Festival; it has been a favorite of Craig's since he first heard it played by Christopher Monk and Alan Lumsden. [The photo above, right, shows Craig and me at the recording session for the duet at Symphony Hall, Boston. Photo by Stephen E. Gerber.] This duet has the distinction of having a high b flat in the second (lower) part (played by Craig), an unusually high note for the serpent which Craig executes splendidly. Craig is an able duet partner and playing with him was great fun. With the two of us alone on the Symphony Hall stage, we would pause after each take and listen to the unique sound of two solo serpents reverberating in one of the great rooms for music in the world.

The music to this duet came to me courtesy the Christopher Monk Collection. It was included in his book, "The Serpent Player," transposed by Monk from the original key of G to F (disputes about pitch, and whether or not historical serpents which today play in C were, at the time they were made, played in D, leads serpentists to, from time to time, transpose etudes and duets by a step allowing them to lie more comfortably on the instrument).

Henri Du Mont (1610-1684) is best known as a composer of sacred motets and a series of five "Masses in plain chant" (Messe royale). Trained as an organist and

bassoonist, Du Mont held various positions in France (having been born in Holland and granted French citizenship in 1647) including organist to the

Queen (1660) and compositeur de musique de la chapelle royale.

The popularity of Du Mont's work was great both during his lifetime and throughout the 18th and 19th centuries. In the case of Du Mont's five Masses,

a serpent player would have doubled the cantus firums; in fact, Canon Galpin (of Galpin Society fame) reported hearing one of these monophonic masses,

with serpent accompaniment, played in a provincial French church as late as the 1920's.

Given that chant was so vital to the musical life of the serpent from its earliest beginnings, including a work which came from the first century of the serpent's existence seemed a logical thing. Peter Wilton [Shown at right, photo courtesy Craig Kridel], British chant scholar and Director of Music of The Gregorian Association, was commissioned by Berlioz Historical Brass to realize a performance edition (for choir, organ and implied serpent) of the first Messe Royale in the chant sur le livre style. The Credo is adapted from serpentist Jean-Baptise Métoyen's early 19th century treatise, Recueil de chants d'eglise (1810). In the recording of Credo on my CD, I played the cantus firmus part throughout, while the vocal parts were in two or three parts. On June 8, 2003, Peter Wilton's realization of the Messe in Plainchant (Royale), Premier Ton was premiered at St. Etheldreda's Church, London, with Craig Kridel and Phil Humphries playing serpent. [Photo above, left: Peter Wilton and Phil Humphries (serpent) at St. Etheldra's Church, London. Photo © Craig Kridel. All rights reserved. Used with permission.]

Recording this strong statement of the Christian faith with Gloriæ Dei Cantores Schola was a thrill. As we were recording in the Church of the Transfiguration, surrounded with stunning new frescos, mosaics and other sacred works of art, the Credo came alive in a new way. Such commitment and passion I have never heard in a choir before. The Gloriæ Dei Cantores Schola left me with a magnificant impression and wonderful memories of a very, very special moment in time.

Harmoniemusik (that is music for harmonie, or wind, ensemble) has been a part of the musical scene for many centuries. In the days before radio and recordings, the only way to hear music was to perform it, so "house music" was a nearly essential element of any "refined" family. For the royalty, hiring ensembles of musicians to entertain at meals, parties and other functions provided employment to thousands of musicians over the years.

It is also true that before copyright protection and royalty payments, the only way composers could make money from their music was to give concerts and

charge admission for a ticket, or to sell the music outright. Beethoven was one of many composers who allowed his works to be arranged for a variety of ensembles

in order to maximize sales of his music. Sometimes the composer himself would have a hand in making an arrangement (such as Brahms, who originally

arranged his "Variations on a Theme of Haydn" for four hand piano and then later for orchestra) and sometimes they allowed others to make an

arrangement on their behalf.

It is also true that before copyright protection and royalty payments, the only way composers could make money from their music was to give concerts and

charge admission for a ticket, or to sell the music outright. Beethoven was one of many composers who allowed his works to be arranged for a variety of ensembles

in order to maximize sales of his music. Sometimes the composer himself would have a hand in making an arrangement (such as Brahms, who originally

arranged his "Variations on a Theme of Haydn" for four hand piano and then later for orchestra) and sometimes they allowed others to make an

arrangement on their behalf.

Beethoven's Symphony 7, premiered in 1813, was published in Vienna in 1816, and at the same time the orchestral version was published, versions for wind ensemble, piano trio, string quartet, piano, and four hand piano were also released. It is not known who made the arrangement for harmonie ensemble, but the publisher, Steiner und Comp., Vienna, also published the orchestral version. While speculation holds that Georg Druschetzky may have made the arrangement, there is no firm evidence to support this. Several modern editions of this historical arrangement have been published more recently.

The instrumentation for the harmonie version of the Symphony 7 of Beethoven is pairs of oboes, clarinets, horns and bassoons, with

the addition of a contrabassoon. While the "standard" instrumentation of such works for winds was for eight instruments, a ninth instrument was often

added to reinforce the bass line, or to allow the bassoons to have parts independent of the bass line. Even in Beethoven's time the contrabassoon was somewhat

of a rarity, so in performance, any available low bass instrument might be substituted if it was on hand and a competent player could be found.

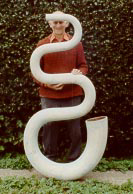

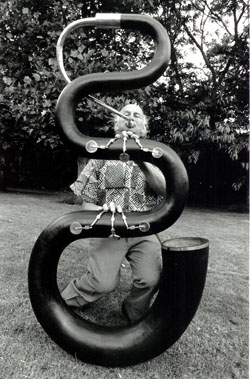

Several years ago I became aware of the fact that an extraordinary contrabass serpent had been made in 1840 in Huddersfield, England, by two brothers whose last name was "Wood." This instrument, now in the Edinburgh University Collection of Historic Musical Instruments (which has a stunning online catalog, and an entire page devoted to this contrabass serpent, complete with photos and sound files played by Andrew van der Beek), is an extraordinary thing [Photo above, left, of Douglas Yeo with the original "Anaconda"; Photo above, right of Christopher Monk with "George" before the leather and keys were applied. Photo courtesy of Craig Kridel. ]. Dubbed the "Anaconda," it is still playable and has most often been played by Andrew van der Beek who played it on concerts and recordings with the London Serpent Trio. The "Anaconda's" most famous appearance was at the Hoffnung Music Festival Concert held in Royal Festival Hall, London, on November 13, 1956, where it was featured in Gordon Jacob's "Variations on 'Annie Laurie'" Jacob's "Variations" were scored for a peculiar instrumental line up, including two piccolos, heckelphone, two contrabass clarinets, two contrabassoons, serpent (played by Eric Halfpenny), contrabass serpent, (played by Nigel Amherst), harmonium, hurdy-gurdy and subcontrabass tuba. Unfortunately, the "Anaconda" was damaged during that concert and it fell to Christopher Monk to subsequently make repairs to the instrument.

Christopher Monk was not the kind of person known to leave well enough alone. Monk never forgot the beloved "Anaconda" and when Philip Palmer,

a musicologist, performer and collector asked Monk to make a contrabass serpent for him, Monk undertook what was perhaps his greatest challenge and what

would be one the last instruments he would make before his death in 1991. [Photo below, left, of Philip Palmer in front of his display case of brass instruments

including serpents and ophicleides. Photo, right, of Christopher Monk in his workshop nearing completion of construction of "George." Photo courtesy of Christopher Monk's

daughter, Philippa Monk Lunn.]

Christopher Monk was not the kind of person known to leave well enough alone. Monk never forgot the beloved "Anaconda" and when Philip Palmer,

a musicologist, performer and collector asked Monk to make a contrabass serpent for him, Monk undertook what was perhaps his greatest challenge and what

would be one the last instruments he would make before his death in 1991. [Photo below, left, of Philip Palmer in front of his display case of brass instruments

including serpents and ophicleides. Photo, right, of Christopher Monk in his workshop nearing completion of construction of "George." Photo courtesy of Christopher Monk's

daughter, Philippa Monk Lunn.]

Instead of attempting to copy the original "Anaconda" contrabass serpent (which, by construction, is really more of a wooden ophicleide, with its holes varying in size and each hole having a "chimney" covered by a key), Monk decided to make a double size copy of his Baudouin church serpent. This instrument, which came to be known as "George" as it first came to life on St. George's Day (April 23) in 1990, was a singular achievement. At the time of the sale of the instrument to Philip Palmer, Monk drew up a sheet of "vital statistics" about "George":

"George" made his first public appearance at the Serpent Festival of 1990 held at St. John's, Smith Square, London, and was subsequently shipped to Philip Palmer

in July 1990. Philip Palmer was an enthusiastic serpentist, who received his PhD in Musicology from Columbia Pacific University with his

dissertation, "The Serpent: An Historical Survey of the Instrument and its Literature, Performance Practice and Problems, and Past and Present Uses." His

paper was later modified and printed in the Historic Brass Society Journal 2, 1990, under the title, "In Defense of the Serpent." With his wife, Connie,

and friends Robert and Tra Wageknecht, Phil Palmer formed the "Saturday Serpent Society" which met to play serpent ensembles for pleasure and

performance.

After Philip Palmer's death, his wife Connie preserved his collection of brass instruments. Just as I was beginning my foray into the world of the serpent in 1994, I had several telephone conversations with Philip Palmer and he was extraordinarily helpful in pointing me to people who could assist me on my journey with the serpent. When I was asked to give a presentation about the serpent at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts in April 1998, I recalled my conversations with Philip Palmer and inquired of Connie if I could borrow "George" as I was sure that my MFA demonstration would be made all the more interesting by including a contrabass serpent. Connie graciously agreed, and "George" was a big hit at the Museum of Fine Arts. That summer, I organized a concert of Harmonie musik at Tanglewood, the Boston Symphony's summer festival home on which I decided to perform the Allegretto from Symphony 7 of Beethoven. [Photo at right of Douglas Yeo with "George" and the soprano serpent, nicknamed the "Worm" made by Christopher Monk (formerly from Monk's personal collection), at Tanglewood, July 1997. Photo © Walter Scott. All rights reserved. Courtesy the Boston Symphony Orchestra. Photo, left, of Christopher Monk playing the completed "George." Photo courtesy of Christopher Monk's daughter, Philippa Monk Lunn.]. Substituting the contrabass serpent "George" for the originally notated contrabassoon part was a natural thing to do, and there is no doubt that "George" gives the bass line a beautiful and full bottom.

In 2000, Connie Palmer asked me if I would like to buy "George" and there was no question that I would like to give a new home to this unique and very special instrument. As one of Christopher Monk's last instruments, "George" is a fitting cap on Monk's crown as a serpent maker and a player. From all reports he loved "George" and parting with him was difficult; even as he was ill and near death (which came on July 17, 1991) , he wanted to make another contrabass serpent for himself (Monk's dream came true several years later when Keith Rogers of the Christopher Monk Workshop made another contrabass serpent which has been dubbed "George II" - although its owner, Matthew Bettenson, has said he wishes he could call it "George III" as that monarch was mad...).

In a letter to Philip Palmer dated May 7, 1990, Christopher Monk wrote:

We have kept careful record of the time spent on developing "George" since we began in April 1989. The total man hours so far add up to 677 and will not be less than 750 by the time all is finished. Taking into account material costs running close to four figures, with the best will in the world the price tag can't be less than five thousand sterling. That in fact is allowing a fair share of the development work to be set against the second one I shall be making for myself later this year.This is well above what I had guessed and if it goes beyond what you are prepared to give I shall not be surprised. My chief regret is that it may cause you disappointment. It will in any case be here for the Workshop and Birthday Party to be seen and played. My cancer has ruled out the practicability of making my own by then as had been planned.

No, Christopher Monk, Phil Palmer was not disappointed, and nor have hosts of people who have enjoyed the sight and sound of "George." "George" is indeed a remarkable instrument, and including its sound on my new CD gave me the greatest of pleasure.

While there had been serpentists who had made something of a solo career, like the celebrated player André who was a member of various English royal

bands in the 18th century and performed a Corelli doublebass Concerto on the serpent, it was not until 1987 that the serpent had a proper concerto of its own.

Craig tells the story of how the Serpent Concerto came to be:

The Proctor Serpent Concerto was written in the autumn of 1987 while Simon was spending a sabbatical at the University of South Carolina - actually, Simon wanted to "experience American culture," so he came over [from England] and lived with me for four months. The work was "commissioned by United Serpents" [the international Serpent "club" whose mottos is "People Like US"] and it is dedicated to Alan Lumsden [a member of the London Serpent Trio]. The Serpent Concerto received its world premiere on Oct. 21, 1989 at the First International Serpent Festival (celebrating the 399th anniversary of the serpent). Alan Lumsden was the soloist with The University of South Carolina Chamber Orchestra under the direction of Donald Portnoy.

In three connected movements, the Serpent Concerto is surely the most difficult original work ever composed for serpent. While Simon Proctor became well acquainted with the capabilities (and limitations) of the serpent, he did not write a simple piece for the instrument. Rather, he chose a style which fit the instrument - serious but not too serious, significant but humorous, difficult, but not unnecessarily so.

Simon undertook to first of all exploit the "good notes" of the serpent, which are mostly a variety of F, B flat, C, G and A. Setting up several recurring themes with these notes provides an integrating feature to the piece.

The premiere by Alan Lumsden was the stuff of history. Never before had a Concerto for serpent been heard. Lumsden's nimble technique was an able match

for Proctor's challenge, but he was surely taxed. In fact, after the premiere in 1989, no other serpent player publicly played the piece; it was, for all

intents and purposes, considered unplayable.

Always one to like a challenge, I secured a copy of the Serpent Concerto and promptly agreed with the conventional wisdom: it was indeed unplayable. But that had not stopped me from undertaking other challenges in my life, so I began, in 1996, to attempt to learn Proctor's Serpent Concerto. It proved to be a great journey of self-discovery. By attempting something so difficult, I found out in clear ways what my own limitations were and how I would overcome them. After many months of practice, I felt comfortable performing the Serpent Concerto in public which I did on a recital in New England Conservatory of Music's Jordan Hall on March 31, 1997 with Deborah DeWolf Emery playing piano. Several months later, I had one of the great musical thrills of my life when I played the Serpent Concerto at Symphony Hall in Boston with the Boston Pops Orchestra conducted by John Williams [Photo above, left, of Douglas Yeo, Simon Proctor and John Williams with the Boston Pops Orchestra, May, 1997. Photo by Craig Kridel © Berlioz Historical Brass. All rights reserved. Used with permission.].

Since that thrilling time playing the Serpent Concerto with the Boston Pops Orchestra, I have played the Serpent Concerto with several other orchestras including the Boston Classical Orchestra, the Connecticut Valley Chamber Orchestra, the Wheaton (Illinois) College Symphony orchestra and, most recently, in October 2003, the South Dakota Symphony. Simon's Serpent Concerto remains a thrill to play every time I undertake it. It keeps me honest with the serpent.

In recording the Serpent Concerto for my CD, I decided to record it in the composer's own piano reduction as that is the way most players (and I do hope there will be players who will undertake it!) will perform it. To the piano accompaniment, I decided to add the important part Simon wrote for "medieval bells." While living with Craig Kridel during the time he composed the Serpent Concerto, Simon became fascinated with a set of cupped bells by Whitechapel, London, that Craig had. He wrote that set of bells into the piece and they were used both on the premiere in 1989 and on my new recording. I was very pleased when Craig volunteered to play the bell part himself [Photo above, right, Douglas Yeo, Deborah DeWolfe Emery and Craig Kridel at the recording session for the Proctor "Serpent Concerto" at Symphony Hall, Boston. Photo by Stephen E. Gerber].

Those with especially good ears will detect 8 measures of editing magic; in the finale, there is a spot where two hands on the piano are simply not enough to cover all the themes that Simon has going on at once. Debbie Emery overdubbed herself playing several measures in order to give the recording a fuller measure of what Simon asked for. I won't tell you where those eight measures are, you'll just have to discover that yourself!

Simon Proctor's Serpent Concerto is under contract for publication by Southern Music Company. While it will always be thought of first and foremost as a piece for serpent, there is no doubt it is an attractive work for other bass wind instruments such as bassoon, euphonium and bass trombone. The Serpent Concerto should be published some time in 2004 with the piano reduction; the orchetral parts will be available by rental from Southern Music Company.

The text of the Domine Salvum comes from the Vulgate (Latin) translation of the Bible, in Psalms 19:10:

Lord save the king and hear us in the day when we shall call you.

In most translations, including the King James version, this verse is found in Psalm 20, verse 9, and the translation is something more than a little bit different:

Many French composers set the text to the Domine Salvum, including Hector Berlioz who set it in his Messe solennelle. When Napoleon Bonaparte proclaimed himself emperor of France, he had the text of the Domine Salvum changed to:

Lord save the emperor. . .

With Roze's Domine Salvum, Le Monde du Serpent comes to a prayerful close. Through this journey we have covered several centuries of music history and music making, from France to England and back again to France. The 24 page booklet which accompanies the CD opens with this warm quotation by Thomas Hardy from his, "Under the Greenwood Tree" (1872):

And so it was, and is.

But there is even more. Musicians have many reasons for playing the instruments they play. As I said at the top of this page of program notes, it was my curiosity which led me to first pick up the serpent. Likewise, curiosity led Christopher Monk to do the same. For others it is the inspiration of another person that leads them down a road to try something new. But no matter what the reason, the fact is that once "caught" by the serpent, I have had no end of fun with it. "Fun" is an old-fashioned word. We work hard all day, work hard to raise our children, work hard to make financial ends meet, work hard to have our relationships be healthy. But "fun"? Can something so difficult as playing the serpent really be "fun"?

Yes. Indeed, it is. The serpent has given me a great deal of joy and fun over the years. It is an instrument that instantly captivates the eye of anyone who sees it. Go to any museum with a musical instrument collection and you'll see what I mean. People are always standing around, looking at the serpent. It has that kind of appeal. But while people are looking at it, most are invariably thinking, "What does it sound like?" To answer that question is to give one of the reasons for Le Monde du Serpent. Several years ago, I was in Hamamatsu, Japan, and visited a fine musical instrument museum there. The museum had an audio guide associated with many of the instruments, and you can imagine my surprise when I pushed the button in front of the serpents on display and the London Serpent Trio began playing the March from "Scipio" from their LP "Sweet and Low." Half way around the world, and the London Serpent Trio was there with me. Perhaps someday a museum may use a track from Le Monde du Serpent to similarly inform visitors of the sound of the serpent.

The photo at left tells a story that needs no words. You can see my family [Photo: Left to right: Douglas Yeo with contrabass serpent "George" by Christopher Monk, Linda Yeo with church serpent in C by the Christopher Monk Workshop, Patricia Yeo with tenor serpent ("serpet") by Christopher Monk, Robin Yeo with soprano serpent ("worm") by Christopher Monk)] holding serpents. Apart from me, none of them had ever held a serpent before that photo was taken (in 1997). But look at us! The joy, the laughter, the "fun," the questions being asked - it's all there. And I've seen it time and time again. When I give demonstrations about the serpent, or play the serpent in a recital, or with an orchestra, the eyes of the children tell a brilliant story - wonder, imagination, and a question answered. "Now I know what that sounds like!" And they become acolytes in the cause of spreading the word that the serpent made MUSIC - it was not just something for picture books and museum walls. And the look in that child's eye (or that adult's raised eyebrow and smile) is part of what causes me to carry on and continue to play the serpent. For life is about sharing.

Finally, there is even one more thing. While the serpent is a demanding friend and requires diligence and patience to master it (if, indeed, it can ever be mastered), the daily journey of discovery with it is something quite special and rewarding. It is my hope that Le Monde du Serpent adds something positive to the distinguished history of this fascinating instrument, and that others will enjoy or even perhaps be inspired to take up the "good old note" that is the serpent.

To Christopher Monk and the pioneers which have gone before him over the last 400 years, Requiem aeterna dona eis. The adventure continues.

Return to LE MONDE DU SERPENT Page | Order LE MONDE DU SERPENT | Read reviews of LE MONDE DU SERPENT

|

All rights reserved. |